links

(disambiguation)

(disambiguation)

(alternated prism / antiprism as a snub)

(alternated prism / antiprism as a snub)

(antiprism as a segmentotope with dual bases)

(antiprism as a segmentotope with dual bases)

| Site Map | Polytopes | Dynkin Diagrams | Vertex Figures, etc. | Incidence Matrices | Index |

*) The part about edge-expanded polytopes was derived in a co-operation with J. McNeill (cf. e.g. his pages on EEBs or on n,n,3-acrons).

Also lots of the EKFs provide interesting axial polytopes (although these are not restricted to axial symmetries in general).

(E.g. in 3D cf. n/d-py for general {n/d} base.)

The pyramids are the outcome of the pyramid product. Take any polytope as base, a single point with a relative orthogonal offset. Then the projective scaling, centered at that point, will outline the derived pyramid within the interval from the point up to the given base. At this level nothing is said about dimensions, convexity of the base, nor about edge lengths.

As far as the base polytope is a non-snub, has a Dynkin diagram description and is orbiform, the whole pyramid will have a Dynkin diagram too. At least in the sense of a lace prism with appropriately scaled lacings. Just prefix any node symbol (thus either being an x or a o) by an unringed node (o). And finally postfix the obtained symbol by "&#y", where the relative size of y is a function of the desired height of the pyramid, in fact it provides the lacing length. – Although pyramids can be built on a snubbed base, the required symbol cannot be obtained in the just described way, because the processes of alternation and setting up the pyramid product do not commute. Orbiformity of the base was required, as else those lacings cannot all be of a single length.

The actual height of a pyramid can be calculated by means of theorem of Pythagoras as h = sqrt(|y|2 - r2), where |y| will be the absolute length of the lacing edges and r is the circumradius of the base polytope. For 3D pyramids one further has r( x-n/d-o ) = 1/(2 sin(π d/n)) and therefore, because of x being unit edges,

h( ox-n/d-oo&#x ) = sqrt[1 - 1/(2 sin(π d/n))2]

Generally this gives as restriction for possible base polytopes h > 0 or |y| > r. For those 3D pyramids therefore one derives

h( ox-n/d-oo&#x ) > 0 or 1 > 1/(2 sin(π d/n)) or sin(π d/n) > 1/2 or π d/n > π/6 or n/d < 6

Because of the equivalence x-n/d-o = x-n/(n-d)-o we likewise get n/(n-d) < 6, or in other words finally: 5/6 < n/d < 6.

Pyramids can be seen as segmentotopes, provided they fullfil their required axioms. In this context those boil down to the requirement that the base polytope has to be a polytope with unique circumradius r, which has to be strictly smaller than 1, and all edges are of unit length. Only then the lacings can be chosen to be of unit length as well. Furthermore the circumradius R of the whole pyramid can be provided then in terms of the circumradius r of the base as:

R2 = 1/[4 (1-r2)]

The lacing facet polytopes all clearly are pyramids in turn, in fact they are pyramids based on the facets of the base polytope.

For convex pyramidal segmentotopes we have:

| 1D | oo&#x | pt || pt | line |

| 2D | ox&#x | pt || line | 3g |

| 3D | ox3oo&#x | pt || 3g | tet |

| ox4oo&#x | pt || 4g | squippy (J1) | |

| ox5oo&#x | pt || 5g | peppy (J2) | |

| 4D | ox3oo3oo&#x | pt || tet | pen |

| ox3oo4oo&#x | pt || oct | octpy | |

| ox4oo3oo&#x | pt || cube | cubpy | |

| ox3oo5oo&#x | pt || ike | ikepy | |

| oox4ooo&#x | pt || squippy (J1) | squasc | |

| oox5ooo&#x | pt || peppy (J2) | pesc | |

| ox ox3oo&#x | pt || trip | trippy | |

| ox ox5oo&#x | pt || pip | pippy | |

| - | pt || squap | squappy | |

| - | pt || pap | pappy | |

| - | pt || gyepip (J11) | gyepippy | |

| - | pt || mibdi (J62) | mibdipy | |

| - | pt || teddi (J63) | teddipy |

A special subclass here are multi-pyramids. Again cf. to the pyramid product. Multi-pyramids are not to be miss-understood here in the sense of a bipyramid, i.e. not as tegum sum of a line and a perp base, but rather are meant in the sense of iteratedly applying the pyramid operation instead, thereby adding a further dimension each time. Thus, these figures would be "pt || (pt || (...(pt || base)...))". J. Bowers here introduced a sequence of according names:

Q-pyramid = Q-py, Q-scalene = Q-py-py, Q-tettene = Q-py-py-py, Q-pennene = Q-py-py-py-py, Q-hixene = Q-py-py-py-py-py, ...

Esp. the point-pyramid-pyramid is nothing but a (generally) irregular triangle, which commonly is called a scalene (triangle).

This is, where this sequence derives from.

Some examples then would be:

| dim. | scalenes | tettenes | pennenes | hixenes | ... |

| 2D |

{3} = pt-py-py

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 3D |

tet = line-py-py |

tet = pt-py-py-py |

- |

- |

- |

| 4D |

pen = {3}-py-py squasc = {4}-py-py pesc = {5}-py-py stasc = {5/2}-py-py shasc = {7/2}-py-py ogasc = {8/3}-py-py ... |

pen = line-py-py-py |

pen = pt-py-py-py-py |

- |

- |

| 5D |

hix = tet-py-py octasc = oct-py-py trippasc = trip-py-py quithesc = quith-py-py sissidisc = sissid-py-py squete = squippy-py-py state = stapy-py-py ... |

hix = {3}-py-py-py squete = {4}-py-py-py state = {5/2}-py-py-py ... |

hix = line-py-py-py-py |

hix = pt-py-py-py-py-py |

- |

| 6D |

hop = pen-py-py hexasc = hex-py-py rapesc = rap-py-py tepasc = tepe-py-py triddipasc = triddip-py-py squippypasc = squippyp-py-py octete = octpy-py-py trippete = trippy-py-py squepe = squasc-py-py ... |

hop = tet-py-py-py octete = oct-py-py-py trippete = trip-py-py-py squepe = squippy-py-py-py ... |

hop = {3}-py-py-py-py squepe = {4}-py-py-py-py ... |

hop = line-py-py-py-py-py |

... |

| 7D |

oca = hix-py-py rixasc = rix-py-py taccasc = tac-py-py hinsc = hin-py-py penpasc = penp-py-py rapete = rappy-py-py hexete = hexpy-py-py octepe = octasc-py-py trippepe = trippasc-py-py squix = squete-py-py ... |

oca = pen-py-py-py rapete = rap-py-py-py hexete = hex-py-py-py octepe = octpy-py-py-py trippepe = trippy-py-py-py squix = squasc-py-py-py ... |

oca = tet-py-py-py-py octepe = oct-py-py-py-py trippepe = trip-py-py-py-py squix = squippy-py-py-py-py ... |

oca = {3}-py-py-py-py-py squix = {4}-py-py-py-py-py ... |

... |

| 8D |

geeasc = gee-py-py hexepe = hexesc-py-py rapepe = rapesc-py-py taccete = tacpy-py-py ... |

hexepe = hexpy-py-py-py rapepe = rappy-py-py-py taccete = tac-py-py-py ... |

hexepe = hex-py-py-py-py rapepe = rap-py-py-py-py ... |

... |

... |

Applying here, the above note, that pyramids on orbiform bases with base radius lesser than 1 generally are segmentotopes, could be iterated. At the first level we have the alignment point || base. Scalenes with such an orbiform base generally do allow for a further such description as line || perp base-base. Tettenes with such an orbiform base generally do allow for a third such description as triangle || perp base-base-base. And the general item of that sequance then allows for the description as simplex || perp iterated base.

(E.g. in 3D cf. n/d-p for general {n/d} bases.)

Similar to the pyramids, prisms are the outcome of the prism product of any base polytope with a lacing edge. Again nothing is said in general about dimension, convexity nor edge lengths. In fact, they also can be seen as elongated ditopes.

If the base polytope has any Dynkin diagram description, this product will have one too. Just add a further ringed node (inline: x) to the diagram but no further links. Note, this would work for snubbed base polytopes alike. For non-snubbed ones however, the Dynkin diagram can be rewritten as a lace prism just by doubling any node symbol of the base polytope, and by postfixing a "&#y", where y provides the relative edge length of the lacings. – Again snubbing does not commute with the product. In fact, for 3D prisms, commutation would lead to the antiprisms.

Prisms can be seen as segmentotopes, provided they fullfil the required axioms. In this context those boil down to the requirement, that the base polytope just has to be orbiform. Further, the lacings will have to be of unit length as well. I.e. for the height of prismatic segmentotopes one generally has h = 1.

The lacing facet polytopes all clearly are prisms in turn, in fact they are prisms based on the facets of the base polytope.

For convex prismatic segmentotopes we have:

| 1D |

x o = oo&#x | pt || pt | line |

| 2D |

x x = xx&#x | line || line | 4g |

| 3D |

x x-n-o = xx-n-oo&#x x x4o = xx4oo&#x |

n-g || n-g

4g || 4g |

n-p

cube |

x x-n-x = xx-n-xx&#x | 2n-g || 2n-g | 2n-p | |

| 4D |

x x3o3o = xx3oo3oo&#x | tet || tet | tepe |

x x3x3o = xx3xx3oo&#x | tut || tut | tuttip | |

x x3o4o = xx3oo4oo&#x x o3x3o = oo3xx3oo&#x | oct || oct | ope | |

x o3x4o = oo3xx4oo&#x | co || co | cope | |

x o3o4x = oo3oo4xx&#x | cube || cube | tes | |

x x3x4o = xx3xx4oo&#x x x3x3x = xx3xx3xx&#x | toe || toe | tope | |

x x3o4x = xx3oo4xx&#x | sirco || sirco | sircope | |

x o3x4x = oo3xx4xx&#x | tic || tic | ticcup | |

x x3x4x = xx3xx4xx&#x | girco || girco | sircope | |

x x3o5o = xx3oo5oo&#x x s3s3s | ike || ike | ipe | |

x o3x5o = oo3xx5oo&#x | id || id | iddip | |

x o3o5x = oo3oo5xx&#x | doe || doe | dope | |

x x3x5o = xx3xx5oo&#x | ti || ti | tipe | |

x x3o5x = xx3oo5xx&#x | srid || srid | sriddip | |

x o3x5x = oo3xx5xx&#x | tid || tid | tiddip | |

x x3x5x = xx3xx5xx&#x | grid || grid | griddip | |

x s3s4s | snic || snic | sniccup | |

x s3s5s | snid || snid | sniddip | |

x x x-n-o = xx xx-n-oo&#x | n-p || n-p | 4,n-dip | |

x s-2-s-n-s | n-ap || n-ap | n-appip | |

| all orbiform Johnson solids | J## || J## | J##-p |

Of course, multi-prisms do exist as well. And this not only with respect to several perpendicular axes (as in: prism of (prism of (prism of ...)) ), but also in the sense of larger perpendicular objects than a mere product with a line. Cf. here again to the prism product, then within its full generality.

(E.g. in 3D cf. n/d-ap for general {n/d} bases.)

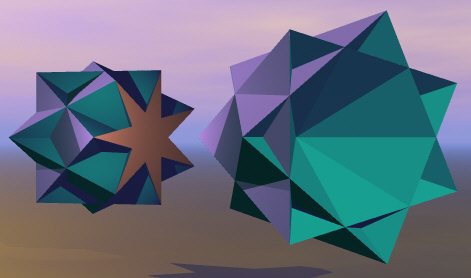

As such an antiprism as such is defined only for 3D. Here it might be described as a gyroelongated dihedron. For an according extrapolation into other dimensions it depends on the chosen construction ansatz, which then gets extrapolated.

• Antiprisms as snubs

Antiprisms within 3D can be derived as the snub (i.e. alternated faceting)

of the prisms with even numbered base polygons. Sure, this concept could be extended to higher dimensions as well,

then being known as Johnson antiprisms. But because of the decreasing relative amount of degrees of freedom when trying to come back to uniform figures

(i.e. equal edge lengths) after the (generally applicable) alternated faceting, this ansatz becomes not too effective.

(Rare examples in that sense would be sidtidap and gidtidap.)

• Antiprisms as segmentotopes with dual bases

An alternate idea would be to consider the base polygons of 3D antiprisms as a dual pair of regular polytopes.

This ansatz, via lace prisms, clearly extends to any dimension,

for 1D it just is point || point and therefore identical to the prism itself, but beyond one uses any linear reflection group graph,

assigns for the top layer (left symbol at each node position of the graph) the ringed node "x" at the left-most position,

while all others will be marked "o"; for the bottom layer (right symbol at each node position) the ringed node

"x" then will be placed at the right-most position, and again all others will be marked "o".

Finally this Dynkin diagram gets postfixed by "&#y", where y gives the relative length of the lacing edges.

– As an aside, extending beyond the topic of axials, this ansatz furthermore could be extended onto n-dental reflection group diagrams

as well, replacing the lace prisms by (n layered) lace simplices, with a single ringed node at a different end for each layer.

|

External links |

(disambiguation)

(disambiguation)

(alternated prism / antiprism as a snub)

(alternated prism / antiprism as a snub)

(antiprism as a segmentotope with dual bases)

(antiprism as a segmentotope with dual bases)

|

It should be emphasized here, by taking dual pairs of regular polytopes, the bases generally will not be the same polytopes, i.e. the top-bottom symmetry generally is lost. It is retained only whenever those are a self-dual pair (as this was the case for any regular polygon).

Sometimes antiprisms with lateral facet pyramids, which do cross the axis of global symmetry, are also called retroprisms. E.g. for the 5/2-ap the lateral triangles don't, whereas for 5/3-ap they do.

Whenever those lacing edges can be chosen to be of the same length as the ones of the base polytopes, we will have a valid segmentotope. Just as for any segmentotope, the lacing facet polytopes all will be segmentotopes in turn. In fact their bases always will be co-dimensional: vertex atop facet (i.e. bottom-up pyramids), edge atop ridge, etc. ..., ridge atop edge, facet atop vertex (i.e. top-down pyramids).

The height of a (uniform) 3D antiprism can be calculated using the polygonal circumradius r( x-n/d-o ) = 1/(2 sin(π d/n)), the inradius ρ( x-n/d-o ) = sqrt[r2 - (1/2)2] = 1/(2 tan(π d/n)) and the height of the lacing triangle h( x3o ) = r( x3o ) + ρ( x3o ) = sqrt(3)/2

h( xo-n/d-ox&#x ) = sqrt[(r( x-n/d-o ) - ρ( x-n/d-o ))2 - (h( x3o ))2] = sqrt[(1 + 2 cos(π d/n))/(2 + 2 cos(π d/n))]

For convex antiprismatic segmentotopes we have:

| 1D | oo&#x | pt || pt | 4g |

| 2D | xx&#x | line || line | 4g |

| 3D |

xo-n-ox&#x xo ox&#x xo3ox&#x |

n-g || dual n-g line || perp line 3g || dual 3g |

n-ap tet oct |

| 4D | xo3oo3ox&#x | tet || dual tet | hex |

| xo3oo4ox&#x | oct || cube | octacube (alt.: octap) | |

| xo3oo5ox&#x | ike || doe | ikadoe (alt.: ikap) |

Alterprisms are just a special case of lace prisms and somehow closely related to a further 3D concept of antiprisms. In fact, a lace prism (in the more specific sense of the term) generally is some A || B, where both A and B both are given wrt. the same symmetry group. Within this setting then an alterprism would be such an lace prism, where B=A again, but would be not a mere prism – in fact we can distinguish here several subcases:

• Base polytope allows for a different orientation within the same axial symmetry

This type of alterprisms occurs for axial stacks of a symmetry group with an additional outer symmetry of the (undecorated) Dynkin graph.

E.g. for linear Dynkin graphs with additional reflection symmetry. Or for tridental graphs with additional rotation symmetry around the bifurcation node

or at least with a mirror symmetry between 2 of its legs.

(Wrt. the first mentioned group, the linear ones, it becomes clear, that antiprisms with self-dual bases will be alterprisms as well.)

• Both base polytopes are still aligned in the same orientation, but allow for a shorter height of separation than the mere prism

This would be the case, when the lacing edges won't connect each top vertex with the one directly underneath (as for the prism), but rather a different one instead.

Examples here would be all the 3D polygrammic antiprisms with even denomiator, but also the Johnson antiprisms

with non-chiral bases. Still, there are further such known cases:

|

External links |

|

For obvious reasons all these alterprisms (of either type) are at least scaliform (in its inclusive sense). Therefore lots of examples are provided on that according page. The most prominent one for sure is the first known scaliform polytope itself, tut || inv tut, which, in the sense of mere lace prisms has been nicknamed "tut-al-tut" (... atop alternated ...), but now can abreviated even shorter to "tut-a" (... alterprism).

Multiple applications of alterprismation will result in an altersquarism, an altercubism, an altertessism, etc. Even so there is a severe restriction to altersquarisms and beyond: the height of the according alterprism itself is bound to be 1/sqrt(2), for else the diagonals of the according lace city display would not have the right size for additional edges (when all unit edged figures are to be considered).

So for instance the altersquarism of tet is evidently possible: as the alterprism of tet happens to be hex and the alterprism of hex is just hin. Therefore hin is nothing but the altersquarism of tet. The same holds true for all the other hemicubes too: the alter-n-hypercubism of a m-hemihypercube is just the n+m-hemihypercube! But, nonetheless, this works beyond as well. Consider for instance tutas (aka: pexhin), which is the altersquarism of tut, or ritas is the altersquarism of rit.

Finally a further extension should be mentioned within this context, although no longer belonging truely to axial polytopes. Consider the alterprisms with an axial symmetry group with an additional outer symmetry of the (undecorated) Dynkin graph, which is not only a mere reflection. This applies in the realm of finite polytopes e.g. for the 4D tridental Dynkin diagrams o3o3o *b3o or for the 3D cyclical Dynkin diagrams o5/2o5/2o5/2*a. Those also allow for some rotational or gyrational symmetry, this time by 120° within the diagrammal representation space. Accordingly we no longer could stay with the mere stack of 2 mutually gyrated copies, but we well can consider the simplicial (here: trigonal) arrangement of all gyrated versions at the same time. Here we consider a 4D resp. 3D "base" space of respective layers and a further 2D position space for the lace city. Accordingly those here described polytopes then would live within 6D resp. 5D. – As alterprisms with symmetrical (undecorated) base diagrams in this view well could be considered gyroprisms, that considered extended class of polypetons resp. polyterons thus generally is called the one of gyrotrigonisms.

Right as it is true for the all the gyroprisms, these gyrotrigonisms too all happen to be scaliform, because obviously all vertices do fall into a single orbit of global symmetry. Moreover, because a trigon clearly is a 2D segmentotope, these gyrotrigonisms could be seen as a monostratic stack of one such 4D resp. 3D base atop of a 5D resp. 4D gyrostack of the 2 other such bases. Accordingly these gyrotrigonisms all qualify furthermore as convex segmentopeta resp. non-convex segmentotera. – Despite of this involved description, there happen to be just 4 gyrotrigonisms within 6D in total. These are named according to their respective base polychora as hexgyt (aka: tedjak), thexgyt (aka: pextedjak), ritgyt, and tahgyt. Because the undecorated 3D base diagram belongs to Grünbaumian figures only, the according 5D gyrotrigonisms likewise would become Grünbaumian in the first run. However there are their respectingly according reductions as well. This then provides 2 more (non-Grünbaumian) gyrotrigonisms: hossidgyt and hodidgyt.

As an aside it should be noted that the further 3D finite cyclical symmetry o5/4o5/4o5/4*a does not allow for gyroprisms because according heights then would become imaginary and that thence gyrotrigonisms are not possible either.

However, this concept in 2022 then got continued conceptually with 7D gyro-octahedronisms (like hexgyo (aka: odinaq), ritgyo,...), where each oriented "base" is "positioned" at the axial ends of an oct of position space, gyro-cuboctahedronisms (like hexgyco (aka: ihdlaq), ritgyco,...), and 8D gyro-icositetrachoronisms (like hexgyi (aka: codify),...), where each oriented "base" is "positioned" at all vertices of either of the 3 ico-inscribed q-hexes. (Although, as their alternate acronyms reveil, the base individuals each had already been known independently before.) In fact those all happen to exist only because of the height of there being used 5D gyroprisms of those tridental bases being 1/sqrt(2), because then the diagonals of according altersquarisms become unity and thus get used as further edges. However the height of the 4D gyroprisms of those cyclical bases differs so that the above structures of position space become not possible in those cases.

Moreover, in retrospective, it just occurs that examples for alterprisms could be obtained by using simply 2 out of 3 "layers" of a gyrotrigonism, examples for altersquarisms could be obtained by using simply 2 out of 3 "layers" of a gyro-octahedronism, and examples for altertessisms could be obtained by using simply 2 out of 3 "layers" of a gyro-icositetrachoronisms. (The seeming lack of the altercubism here is because the former 2 subsettings become subdimensional, while the latter is not.)

A further idea for application turned up in 2024 by using the concept of gyrotrigonisms with euclidean components, which then, like in hyperbolic space too, simply count as horocells (or higher dimensional equivalents). Clearly, by construction these would contain both bounded and infinite directions (like a 3D pillar): the former being built by the position subspace, i.e. the triangular cross-section in case of trigonisms, while the latter is due to the here infinite object subspace. The simplest such figures would be tratgyt and thatgyt. But also the symmetry E6+ would allow for several further such cases, like jakohgyt or rojkohgyt.

As mentioned above, with respect to euclidean tesselations gyrotrigonisms are well possible. However, the infinite reach of the being used tesselations within the individual objects at their lace city contrasts to the orthogonal finite reach of the trigonal arrangement in that position space. Thus it becomes clear that such euclidean gyrotrigonisms happen to describe infinite long triangular needles only. But then one might stack these needles according to a triangular tiling in this position space instead, thus filling in thereby all of the being spanned euclidean space fully again, while blending out their coinciding boundary elements instead. This is, what in 2025 got the name gyro-tratism. As an example it just happens that the gyrotratism of trat itself becomes nothing but hext.

(E.g. in 3D cf. n/d-cu for general {n/d} and {2n/d} bases.)

As such a cupola is defined only for 3D. Although it is ment as monostratic face-parallel top-section of larger (uniform) polyhedra, it is best defined directly as lace prism xx-n/d-ox&#y. As such, the cupola is nothing but a Stott expansion of the pyramid (as the first node position changes from "oo" to "xx"), accordingly for y = x we get the same heights, i.e. h( xx-n/d-ox&#x ) = h( oo-n/d-ox&#x ), and therefrom the same restriction: 6/5 < n/d < 6. Further the base polygon, in order to not become a Grünbaumian double cover, requires d to be odd.

In order to extrapolate cupolas into spaces of higher dimensions, there are different valid possibilities, even within the realm of segmentotopes:

This extrapolation is based on the observation, that the bottom polytope is the kernel of intersection of a dual pair of the top polytope. (Here the base x-n/d-x of a 3D cupola is read as being the kernel of the compound of x-n/d-o with o-n/d-x.) Speaking of dual, the top figures here will be restricted to regular polytopes. Dealing with their Dynkin diagrams those kernels of intersection, (as is described in the truncation series) in case of odd dimensional top facets, just have the single middle node ringed, resp., for even dimensional top facets, just the two central nodes ringed.

For according segmentochora xPoQo || oPxQo, i.e. the lace prisms xoPoxQoo&#x, the lacings thus would be antiprisms (as subdiagrams: xoPox ..&#x) and pyramids (as: .. oxQoo&#x) only.

This different extrapolation sticks to the idea of being a cap of a larger uniform polytope. It also starts with regular polytopes for top facets, but asking the bottom facet being the corresponding Stott expanded version, i.e. its Dynkin diagram has both end nodes ringed. The Dynkin diagram of that larger uniform polytope (of which the cupola would be a cap of) furthermore could be derived by adding "...3x" to the diagram of the top facet.

The accordingly extrapolated segmentochora xPoQo || xPoQx, i.e. the lace prisms xxPooQox&#x have for lacing facets prisms (as subdiagrams: xxPoo ..&#x), trips (as: xx .. ox&#x, i.e. used as digonal 3D cupola in here), and pyramids (as: .. ooQox&#x). Those then would be the xPoQo-cap of the polychoron xPoQo3x.

Other authors like to stick to the 3D axial segment to be an according cupola, while the higher-dimensional tail of the Dynkin diagram remains unringed. I.e. here we would have esp. xPoQo || xPxQo to be "the" 4D cupolae, then having as lacing facets these said cupolae xxPox ..&#x in turn and pyramids .. oxQoo&#x.

It should be noted, that in a much looser sense, sometimes any possible monostratic stacking of Dynkin symbols, i.e. any lace prism, with non-degenerate bases (esp. neither pyramid nor wedge), which not qualifies as prism or other more specific terms (e.g. not an antiprism), might be termed "cupola".

Case A) is the reading of the term "cupola", which the author prefers. For case of B) the author rather prefers the term cap instead. Noteworthy type C) clearly can start for 3D only (the 3D cupolae themselves) and additionally would have even less entries for spherical space. Finally D) is mentioned here for awareness only, and not too much endorsed by the author.

For convex cupolaic segmentotopes we have:

| A | B | C | ||||||||||

| 1D | oo&#x | pt || pt | line | (same: line = pt-cap of line itself) | (impossible, because no axial cupolae) | |||||||

| 2D | xx&#x | line || line | 4g | (same: 4g = line-cap of 4g itself) | (impossible, because no axial cupolae) | |||||||

| 3D | xx ox&#x | line || 4g | trip | (same: trip = line-cap of trip itself) | (same: trip, by definition) | |||||||

| xx3ox&#x | 3g || 6g | tricu | (same: tricu = 3g-cap of co) | (same: tricu, by definition) | ||||||||

| xx4ox&#x | 4g || 8g | squacu | (same: squacu = 4g-cap of sirco) | (same: squacu, by definition) | ||||||||

| xx5ox&#x | 5g || 10g | pecu | (same: pecu = 5g-cap of srid) | (same: pecu, by definition) | ||||||||

| 4D | xo ox3oo&#x | line || perp {3} | pen | xx oo3ox&#x | line || trip | tepe (line-cap of tepe itself) | xx ox3oo&#x | line || trip | tepe (again) | |||

| xo ox4oo&#x | line || perp {4} | squasc | xx oo4ox&#x | line || cube | squippyp (line-cap of squippyp itself) | xx ox4oo&#x | line || cube | squippyp (again) | ||||

| xo ox5oo&#x | line || perp {5} | pesc | xx oo5ox&#x | line || pip | peppyp (line-cap of peppyp itself) | xx ox5oo&#x | line || pip | peppyp (again) | ||||

| xo3ox oo&#x | 3g || dual 3g | (subdimensional: oct) | xx3oo ox&#x | 3g || trip | triddip (3g-cap of triddip itself) | xx3ox oo&#x | 3g || 6g | (subdimensional: tricu) | ||||

| xo3ox3oo&#x | tet || oct | rap | xx3oo3ox&#x | tet || co | (tet-cap of spid) | xx3ox3oo&#x | tet || tut | (tet-cap of rit) | ||||

| xo3ox4oo&#x | oct || co | (oct-cap of ico) | xx3oo4ox&#x | oct || sirco | (oct-cap of spic) |

(unit lacing impossible in spherical space: xx3ox4oo&#x would be the flat octatoe) | ||||||

| xo3ox5oo&#x | ike || id | (ike-cap of rox) |

(unit lacing impossible in spherical space: xx3oo5ox&#x would be the hyperbolic ike-cap of x3o5o3o) |

(unit lacing impossible in spherical space: xx3ox5oo&#x would be the hyperbolic ike-cap of o4x3o5o) | ||||||||

| xo4ox oo&#x | 4g || dual 4g | (subdimensional: squap) | xx4oo ox&#x | 4g || cube | tisdip (4g-cap of tisdip itself) | xx4ox oo&#x | 4g || 8g | (subdimensional: squacu) | ||||

| xo4ox3oo&#x | cube || co | xx4oo3ox&#x | cube || sirco | (cube-cap of sidpith) |

(unit lacing impossible in spherical space: xx4ox3oo&#x would be the flat cubatic) | |||||||

| xo5ox oo&#x | 5g || dual 5g | (subdimensional: pap) | xx5oo ox&#x | 5g || pip | trapedip (5g-cap of trapedip itself) | xx5ox oo&#x | 5g || 10g | (subdimensional: pecu) | ||||

| xo5ox3oo&#x | doe || id | xx5oo3ox&#x | doe || srid | (cube-cap of sidpixhi) |

(unit lacing impossible in spherical space: xx5ox3oo&#x would be the hyperbolic doe-cap of x3o3o *b5x) | |||||||

Cuploids are a completely 3D specific concept. They are somehow related to several of the uniform polyhedra, which do not emanate directly by Wythoff's construction, but in fact are reduced forms of Grünbaumian polyhedra. The same holds true here: as pointed out above, the denominator d of the top polygon x-n/d-o has to be odd, else the cupola gets a Grünbaumian double-cover polygon for bottom base. Exactly in those prohibited cases, i.e. for d being even, that offending face will just be withdrawn, and the open but pairwise coincident edges will be reconnected in the obvious way.

|

This picture, showing a {7/4}-cuploid, reflected in a mirror, was rendered by C. Tuveson in 2001 in reply to a post of mine: "But your structure reminds me to a true polyhedron with a {7/2}-heptagrammic edge circuit at the bottom and a {7/3}-face at the top side, joined to one another by squares plus trigons (the latter pointing towards the vertices of the top-face). It is the retrograd {7/3}-cuploid, or might also be called the {7/4}-cuploid. As it is well known, the bottom-face of a {n/d}-cupola is a {(2n)/d}; but for 7/4 this becomes the reducible number 14/4, which is nothing but the (reduced) {7/2} with a double circuit. Thereby the latteral sides (squares and trigons) join at the bottom edges, and the bottom face is obsolete (or would have to be counted twice, giving rise to pairwise coincident edges)." |

It should be noted additionally that, as long as the top face is not retrograde, i.e. as long as n/d > 2, central parts of the top base offers both sides to the outside because of the bottom base reduction. Faces having this property generally are called membranes.

Within the bounds, also provided above, cuploids exist as segmentohedra. Their bottom face just will have to be marked "pseudo". As this adjective is not transferable into Dynkin diagrams, a lace prism description does not exist. Further, as d has to be even and thus n/d can no longer be integral, clearly there is no convex segmentotope. – As (non-convex) examples thah = {3/2} || pseudo {6/2} and stiscu = {5/2} || pseudo {10/2} might serve. Within 4D there is firp = tet || pseudo 2thah and the co retro-cuploid = co || pseudo 2oct+6{4}.

Also being ment for 3D in the first run, those are miming the cuploids in the complemental cases, i.e. for d being odd again. In those cases nomal cupolas do exist. Sure, in a locally similar manner, 2 copies each can be blended in an axially gyrated way. This blending operation thereby withdraws the doubled up bottom face, while the top face becomes a regular compound. (Although those clearly are segmentotopes, those top face compounds will not be convex.) The easiest ones here are:

Nonetheless, this type of operation surely might look to apply also to pairs of (either way) higher dimensionally extrapolated cupolas with dual top bases. But because then those dual top bases generally no longer have the same circumradius, the height of the to be blended cupolas too must no longer be the same. Thus the top bases then generally would not result in a compound but are arranged in parallel layers, i.e. the blend would not be monostratic anymore. Therefore the research for cupolaic blend segmentotopes (i.e. being monostratic) would have to restrict to top bases which are selfdual only (or otherwise would assure to have the same circumradius). Examples here are

Clearly there is a way to extrapolate at least the Philips head (tutrip) into higher dimensions. However the bottom base dimension then corresponds to the number of orthogonally being blended hypercubes, so that for odd dimensions that very bottom base no longer would result in a hollow figure. Moreover those polytopes then would become wild, because e.g. within 4D the square and the triangle of a latteral tutrip and a square of the bottom cube all are incident to a common edge and thereby still are corealmic. Within 4D we have 2 such extrapolations, the blend of 3 squippyps ("coord-axes edge star" || cube) and the somewhat taller blend of 3 tisdips ("coord-planes square star" || cube). As a third possibility the then non-wild blend of 3 squafs ("thah-squares star" || cube) is to be added here.

But then there is a further application of this very concept of cupolaic blends into higher dimensions as well. Note that the main 3D examples shown within the picture above all have in common that one base of the to be blended identical components has some symmetry which the other base does not have. Within the examples of the picture those are an halved angle of axial rotation. In April 2023 a similar applications of this concept got found for 4D:

Shortly thereafter it even was driven into 5D as well:

Fastegium here derives from latin fastigium, the pediment. Accordingly, as arbitrary dimensional analogue just

Thus, written as a lace prism, it is just oy ...xx...&#z, where x, y, z all define edges of possibly different lengths. The lacing facets accordingly are 2 prisms, similar the bottom one, but now with lacing edges z (while the bottom one has y-lacings), plus, as far as the starting figure had any facets itself, the subdimensional fastegiums derived by those. (Sometimes even the top layer is allowed to differ in size, yielding oy ...wx...&#z.) So, fastegia are special cases of wedges.

If z = y (and w = x) this figure can be rewritten as lace simplex or even as duoprism. oy ...xx...&#y = ...xxx...&#y = y3o ...x.... If further all edges have equal size and the starting polytope was some orbiform, say Q, then the fastegium will be a valid segmentotope (in fact Q || Q-p). Accordingly the segmentotopal height then generally will be h = sqrt(3)/2.

Moreover, whenever Q would be additionally uniform, then the fastegium clearly will be uniform itself, being nothing but the 3,Q-dip.

For convex fastegmal segmentotopes we have:

| 2D |

ox oo&#x = ooo&#x = x3o o | pt || line | {3} |

| 3D |

ox xx&#x = xxx&#x = x3o x | line || {4} | trip |

| 4D |

ox xx-n-oo&#x = xxx-n-ooo&#x = x3o x-n-o | {n} || n-p | 3,n-dip |

This small table already shows, provided P would be any convex, unit-edged, and orbiform polytope of any dimension, that the set of convex fastegmal segmentotopes could equivalently be described as the set of according 3,P-duoprisms.

The antifastegium is essentially built the same way as a (normal) fastegium, just that its subdimensional top layer polytope is replaced by its dual. Speaking of duals, this already asks the starting figure itself to be a regular polytope. Those generally are Wythoffian and therefore moreover orbiform.

Any antifastegium can be written as lace prism, which is oy xo...ox&#z in general, where again x, y, z all define edges of possibly different lengths. The facets of an antifastegium are its bottom prism (.y) (.o)...(.x), the 2 antiprism connecting either bottom base to the top base .. xo...ox&#z, and finally for any other sub-element of the bottom prism there will by an according co-dimensional sub-element of the top base, which has to be adjoined.

Finally, antifastegia which have unit edges only, clearly are segmentotopes.

For convex antifastegmal segmentotopes we have:

| 2D |

ox oo&#x = ooo&#x | pt || line | {3} |

| 3D |

ox xx&#x = xxx&#x | line || {4} | trip |

| 4D |

ox xo-n-ox&#x = xxo-n-oox&#x | {n} || gyro n-p | n-af |

| 5D |

ox xo3oo3ox&#x = xxo3ooo3oox&#x | tet || inv. tepe | tetaf |

| 6D |

ox xo3oo3oo3ox&#x = xxo3ooo3ooo3oox&#x | pen || inv. penp | penaf |

ox xo3oo4oo3ox&#x = xxo3ooo4ooo3oox&#x | ico || inv. icope | icaf | |

| 7D |

ox xo3oo3oo3oo3ox&#x = xxo3ooo3ooo3ooo3oox&#x | hix || inv. hixip | hixaf |

(The more general, not necessarily convex case of 4D then is the n/d-af. Various individual examples then are provided in those general group with links each.)

Quite similar as for the antiprisms there has been an extension towards non-regular bases by means of the term of alterprisms. Here too we could define alterfastegia to be the lace simplex of some polytope (the symmetry group of which has some additional outer symmetry) atop the prism of an alternately oriented version of the same polytope. Accordingly e.g. tutaltuttip could be shortened to "tutaf". Or there even is something like a rappaf, a hexaf, a rixaf, a hinaf, or a jakaf.

A duoantifastegiaprism always can be written as a lace prism in the form xo...ox yo...oy&#z, where again x, y, z all define edges of possibly different lengths. Here the subelements xo...ox&#z and yo...oy&#z would be required to describe antiprisms each. Accordingly the bases here would be required to be (bidually aligned copies of) duoprisms of two regulars each. (In fact, the term duoantifastegiaprism was chosen as a contraction from duoprism duoantifastegium.)

The general convex duoantifastegiaprismal segmentoteron here would be n,m-dafup = xo-n-ox xo-m-ox&#x. In higher dimensions however, the 2 duoprism factors no longer would be bound to equating dimensions. Examples would be the 6D tratetdafup = xo3ox xo3oo3ox&#x or the 7D trapendafup = xo3ox xo3oo3oo3ox&#x and trahex dafup = xo3ox xo3oo3ox *d3oo&#x.

Similarily to the generalization of alterprisms above antiprisms here too the duoantifastegiaprism could be extrapolated a bit, when not being restricted to bases which are duoprisms of regular components only, but allowing for duoprisms of not necessarily regular components as well. Thus then that more general duoantifastegiaprism would require the other layer to be its bi-alternate version (instead of just bi-dual). An example here would be the 7D trarapdafup = xo3ox oo3xo3ox3oo&#x.

A duoantifastegium then can be given as the specific cases, where one of the required subelemental antiprisms becomes a (stretched) tet (xo ox&#z). This clearly makes the duoprisms of the 2 bases degenerate, i.e. the bases would become subdimensional. (This is what reduces one prismatic part from the defining duoprism, and therefore too from the contracted name.)

The general duoantifastegial segmentoteron here would be n/d-daf = xo ox xo-n/d-ox&#x (which moreover is convex for d=1).

As an aside it should be pointed out, that the sequence of used operations (i.e. prism product and stacking) here does not commute: e.g. the number of vertices of (x3o x3o) || (o3x o3x) clearly is (3·3) + (3·3) = 18, whereas (x3o || o3x) (x3o || o3x) would result in (3+3) · (3+3) = 36.

The term duoalterprism was made up as a kind of a false hybrid of the terms of an alterprism and the above duoantifastegiaprism. In fact it is considered to be a tegum sum (instead of the lace prism) of duoprismatic layers as in the latter case, however those needn't be taken as factor-wise antiprisms but rather are allowed to be alterprisms instead. Thus, in short, those could simply be considered to be tegum sums of 2 bi-alternated duoprismatic "layers". Esp. those always happen to be scaliform.

Thence as examples there are e.g.

The bipyramids are the outcome of the tegum product. Take any polytope as a base and a single line segment in orthogonal space, either one being centered at the origin. Then the projective scaling, centered at the ends of the segment, will outline the derived pyramid within the interval from the point up to the given base. At this level nothing is said about dimensions, convexity of the base, nor about edge lengths.

Clearly, bipyramids are closely related to pyramids. In fact those are just external blends of 2 pyramids, being adjoined at their base polytopes. Therefore that defining polytope itself will not be contribute as a true facet of the outcome, as it thereby would be blended out. Yet it can be considered a pseudo face. Likewise it might be possible to dissect the bipyramid into 2 pyramids while squeezing inbetween an equatorial prism. This then is what is meant by elongated bipyramids.

As far as the base polytope is a non-snub, has a Dynkin diagram description and is orbiform, the whole pyramid, bipyramid and even the elongated bipyramids will have a Dynkin diagram too. At least in the sense of a lace tower with appropriately scaled lacings. For bipyramids just pre- and postfix any node symbol (thus either being an x or a o) by an unringed node (o). And finally add to the obtained symbol a final "&#y", where the relative size of y is again a function of the desired height of the pyramid on either side, because literally it provides the lacing length. – Although pyramids can be built on a snubbed base, the required symbol cannot be obtained in the just described way, because the processes of alternation and setting up the tegum product do not commute. Orbiformity of the base was required, as else those lacings cannot all be of a single length.

For convex bipyramids, which generally are external blends of segmentotopes, we have:

| 2D | oqo&#xt | pt || q-line || pt | 4g |

| 3D | oxo3ooo&#xt | pt || 3g || pt | tridpy (J12) |

| oxo4ooo&#xt | pt || 4g || pt | oct | |

| oxo5ooo&#xt | pt || 5g || pt | pedpy (J13) | |

| 4D | oxo3ooo3ooo&#xt | pt || tet || pt | tete |

| oxo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3oxo3ooo&#xt | pt || oct || pt | hex | |

| oxo4ooo3ooo&#xt | pt || cube || pt | cute | |

| oxo3ooo5ooo&#xt | pt || ike || pt | ite | |

| ooxo4oooo&#xr | pt || squippy (J1) || pt | octpy | |

| oxo oxo3ooo&#xt | pt || trip || pt | tript | |

| oxo oxo5ooo&#xt | pt || pip || pt | pipt | |

| - | pt || squap || pt | squapdpy (?) | |

| - | pt || pap || pt | papdpy (?) | |

| - | pt || gyepip (J11) || pt | gyepipdpy (?) | |

| - | pt || mibdi (J62) || pt | mibdidpy (?) | |

| - | pt || teddi (J63) || pt | teddidpy (?) |

(Lately Bowers prefers the acronym suffix X-t, here representing X(,line)-tegum, rather then the older X-dpy.)

As the base angle of a pyramid always is smaller than 90 degrees, an according external blend with a matching prism thus is convex whenever the pyramid itself was.

For convex elongated pyramids, which generally are external blends of segmentotopes, we have e.g.:

| 3D | oxx3ooo&#xt | pt || 3g || 3g | etripy (J7) |

| oxx4ooo&#xt | pt || 4g || 4g | esquipy (J8) | |

| oxx5ooo&#xt | pt || 5g || 5g | epeppy (J9) | |

| 4D | oxx3ooo3ooo&#xt | pt || tet || tet | etepy |

| oxx3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3oxx3ooo&#xt | pt || oct || oct | eoctpy | |

| oxx4ooo3ooo&#xt | pt || cube || cube | ecubpy | |

| oxx3ooo5ooo&#xt | pt || ike || ike | eikepy | |

| oxx oxx3ooo&#xt | pt || trip || trip | etrippy | |

| oxx oxx5ooo&#xt | pt || pip || pip | epippy |

Obviously the same construction as for elongated pyramids applies for their Stott expansions wrt. their across symmetry. This is what is understood within 3D as the well-known elongated cupolas in the set of Johnson solids. But, as has been outlined above, the extension of the meaning of the term cupola is quite ambiguous beyond 3D. In fact, those expansions only would build a subset of the type C cupolas, or would be a superset of the type B cupolas. The type A cupolas on the other hand have to be investigated individually whether the 90 degrees condition is being met for all bottom base angles.

For convex elongated cupolas (in the sense of across symmetrically Stott expanded elongated pyramids), which then generally are external blends of segmentotopes, we have e.g.:

| 3D | oxx3xxx&#xt | 3g || 6g || 6g | etcu (J18) |

| oxx4xxx&#xt | 4g || 8g || 8g | escu (J19) | |

| oxx5xxx&#xt | 5g || 10g || 10g | epcu (J20) | |

| 4D | xoo3oxx4ooo&#xt | oct || co || co | eoctaco |

| xoo3oxx4xxx&#xt | sirco || tic || tic | esircoatic | |

| xoo3oxx5ooo&#xt | ike || id || id | eikaid | |

| xoo3oxx5xxx&#xt | srid || tid || tid | esridatid | |

| oxx3ooo3xxx&#xt | tet || co || co | etetaco | |

| oxx3ooo4xxx&#xt | cube || sirco || sirco | ecuba sirco | |

| oxx4ooo3xxx&#xt | oct || sirco || sirco | eocta sirco | |

| oxx3ooo5xxx&#xt | doe || srid || srid | edoasrid | |

| oxx3xxx3ooo&#xt | oct || tut || tut | eoctatut | |

| oxx3xxx4ooo&#xt | co || toe || toe | ecoatoe | |

| oxx4xxx3ooo&#xt | co || tic || tic | ecoatic | |

| oxx3xxx5ooo&#xt | id || ti || ti | eidati | |

| oxx3xxx3xxx&#xt | tut || toe || toe | etutatoe | |

| oxx3xxx4xxx&#xt | tic || girco || girco | etica girco | |

| oxx4xxx3xxx&#xt | toe || girco || girco | etoa girco | |

| oxx3xxx5xxx&#xt | tid || grid || grid | etidagrid | |

| oxx oxx3xxx&#xt | 3g || hip || hip | etripuf | |

| oxx oxx4xxx&#xt | 4g || op || op | esquipuf | |

| oxx oxx5xxx&#xt | 5g || dip || dip | epepuf |

This concept is meant for 3D and was invented as an infinite series of polyhedra in summer 1999 by the author. It starts with the (exterior) blend of 2 prisms, i.e. the lace tower xxx-n/d-ooo&#xt, with n ≥ 2d (i.e. progrades). This one would be the {n/d}-gonal (0,0)-EEB.

Now unconnect the lacing edges, and insert triangles inbetween the lacing squares. Here generally there are 2 possibilities: either by bending the squares inward, thus looking like an exterior blend at the bottom face of 2 retrograde cupolas (or cuploids), the {n/d}-gonal (exo-) (1,1)-EEB; or by bending the squares outward, thus looking like the corresponding blend of 2 prograde cupolas (or cuploids), {n/d}-gonal (endo-) (1,0)-EEB.

Instead of inserting a single triangle into that lacing gap at either segment, one equally could insert k triangles each. I.e. the base-vertices are [n/d,4,3k,4] (up to windings, see below). While at the central layer there are vertex types [32,42] (for k>0) and [34] (for k>1). Again there are exo- and endo-types, relating to emanating triangles to the relative outside resp. to the inside (best seen in the equatorial section); equivalently exo means that the lacing squares will bend inward, endo describes the cases where those squares bend outward. Here one also speaks of k-extended (exo-/endo-) EEBs.

For k>1 there even are several possibilities when the sequence of the equatorial edges of a square pair, of those inserted triangle pairs, and of the next square pair winds less or more than once around their orthogonal, vertical axis. This winding number w will be the second parameter of the general {n/d}-gonal (k,w)-EEB. Those are restricted to 0 ≤ w ≤ k-1. (In order to get a planar equatorial layer, the bending of the squares will have to be adapted accordingly.) – Here some examples are in place. The following pictures show parts of the base polygons in red, the equatorial edges between the squares in blue, and those between triangles in black.

|

|

|

|

exo (3,0)-EEB, the winding KTSL around O is < 2π |

endo (3,0)-EEB, the winding KTSL around O is < 2π |

endo (3,1)-EEB, the winding KSTL around O is > 2π, but < 2 · 2π |

In order to calculate the height consider the internal vertex angle of the base polygon x-n/d-o. That one is

∠AOB = π(1-2d/n)

For endo-EEBs (with k>0) one adds 2 right angles (∠AOK, ∠LOB) plus 2πw. That total angle then will be devided into k equal parts, each being the angle sustained by any equatorial triangle edge:

∠TOS = 2π(1+w-d/n)/k

On the other hand, for exo-EEBs (with k>0) one has to subtract from ∠AOB those 2 right angles. But one will have to add 2π(w+1) here. Thus the total angle a posteriori will be the same, and so too each angle sustained by any equatorial triangle edge gets the same number as for the endo case.

Using unit edges and the radius of those equatorial vertex circles r = |OK| = |OL| = |OT| = |OS| within the right triangle, which is the half of TOS, one gets r sin(∠TOS/2) = 1/2. On the other hand the total height of the EEB is h = 2 sqrt(1 - r2). Thus (independing of exo- or endo-)

h( {n/d}-gonal (k,w)-EEB ) = sqrt[4 - 1/sin2(π(1+w-d/n)/k)]

This height formula also shows the range of n/d such that for any given value of (k,w) both the exo- or endo-forms of an {n/d}-gonal (k,w)-EEB do exist, i.e. provide a height with h>0.

| clicking the drawings provides the corresponding preview in the canvas right | |

|---|---|

| |

| clicking the drawings provides the corresponding preview in the canvas right | |

|---|---|

| |

Some special cases clearly are the {n/d}-gonal endo (1,0)-EEBs. Those are also known as (prograde) orthobicupola. The special cases n/d = 3/1, 4/1, 5/1 belong to the Johnson solids, in fact those are tobcu (J27), squobcu (J28), resp. pobcu (J30). – The {n/d}-gonal exo (1,0)-EEBs then are the corresponding retrograde orthobicupola, i.e. orthobicupola with top base {n/(n-d)} (with n ≥ 2d).

Other special cases are the {n/d}-gonal endo (2,1)-EEBs. Those are also known as sphenoprisms, i.e. the connection of the bases by (pairs of) triangle-square-triangle sphenoids. The special case n/d=2 here again is a Johnson solid, in fact the esquidpy (J15). But even within the range 2≤n/d<3 all those {n/d}-gonal endo (2,1)-EEBs are at least locally convex. (The limiting case n/d = 3 then would become flat.)

One even could extrapolate EEBs to retrograde {n/d}, i.e. to {n/(n-d)} within the so far assumed prograde bound n ≥ 2d. This extension would switch endo- and exo EEBs. For sure, the parameter k is un-affected. But with w' = k-w-1 one gets the identity

{n/d}-gonal exo (k,w)-EEB = {n/(n-d)}-gonal endo (k,k-w-1)-EEB

{n/d}-gonal endo (k,w)-EEB = {n/(n-d)}-gonal exo (k,k-w-1)-EEB

which shows, that such retrograde bases not truely produce anything new.

© ©

| Just as the EEBs start with the exterior blend of 2 {n/d}-prisms, the EEAs, i.e. edge-expanded antiprisms, are meant to start with the appropriate blend of 2 {n/d}-antiprisms. But, in fact, this would become rather the k=1 cases. We even could start instead by a pair of {n/d}-pyramids, which are mirrored at their tips. This then will become the general {n/d}-gonal (0,0)-EEA. Iterated insertion of triangle pairs at the lacing edges of that bipyramid produces – similar to the EEBs – a new set of {n/d}-gonal exo/endo (k,w)-EEAs. Here the former prism-squares (of the EEBs) clearly are replaced by the lacing antiprism-triangles. – The EEAs where found by J. McNeill. |

| exo {5} (2,0) EEA |

| clicking the drawings provides the corresponding preview in the canvas right | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| clicking the drawings provides the corresponding preview in the canvas right | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

The height can be calculated along the same lines as were shown for the EEBs. The height of the {n/d}-gonal endo (k,w)-EEA reads as follows. (Those for the exo versions could be deduced therefrom by substituting w → w* = k-w-1.)

h( {n/d}-gonal endo (k,w)-EEA ) = sqrt[4 - 1/sin2(π(1+w-d/n)/(k+1))]

h( {n/d}-gonal exo (k,w)-EEA ) = sqrt[4 - 1/sin2(π(k-w-d/n)/(k+1))]

In 2004 A. Weimholt came up with an interesting set of polytopes which later became known as ursatopes (or ursulates). The 3D member of this large family, which since got lots of extensions, is teddi. This is why the whole family (which then will be forced to contain it as sub-dimensional boundary) was named ursatopes.

The general setup here later was mainly elaborated by W. Krieger. In fact, these polytopes derive from a cone where the edges of the bottom base become acute golden triangular sides (i.e. ox&#f) of a pyramid. From that cone one consideres first a section of lacing edge length 2f. The remainder then is a truncation of that pyramid: Chopping off the tip at half of its height, revealing thus the ursatopal bottom base as this crosssection, resp. chopping off the other vertices in such a way, that the remaining lacings get reduced from their f-length down to x-sized edges only, while the pyramidal bottom edges get reduced to zero, i.e. this ursatopal top face will be the rectification of the bottom one. – The new additional lacing edges introduced by the latter choppings by construction will have unit size. But the existence of the to be produced rectification as well as the to be obtained unit edge sizes all over raise some restrictions on the possible ursatopal bottom bases. And also the height of that starting pyramid would be required to be positive.

All this can be cast into the following necessary and sufficient conditions:

These then could be subject to Stott expansions within the across subsymmetry.

The simplexial ursatopes as well as the orthoplexial ones moreover are also enlisted in a more detailed comparision on the dimensional analogs page.

|

across symmetry | ursatopes | comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D | o | ofx&#xt = {5} = peg | vertex figure of s3s4o |

| 3D | o o | ofx xxx&#xt = pip | vertex figure of o3x3o5o |

| o3o | ofx3xoo&#xt = teddi | vertex figure of s3s4o3o | |

| o4o | ofx4qoo&#xt | not orbiform | |

| 4D | o3o o | ofx3xoo xxx&#xt = teddipe | |

| o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo&#xt = tetu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o | |

| ofx3xoo3xxx&#xt = coatutu | |||

|

o3o4o & o3o4/3o | ofx3xoo4ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo4/3ooo&#xt = xoo3ofx3xoo&#xt = octu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o4o | |

| ofx3xoo4xxx&#xt = sirco aticu | |||

| ofx3xoo4/3xxx&#xt = quercoa quithu | |||

| o3o5o | ofx3xoo5ooo&#xt = iku | vertex figure of s3s4o3o5o, diminishing of x3o3o5o | |

| ofx3xoo5xxx&#xt = sridatidu | |||

| xoo3ofx5xox&#xt = tiduro (ursatope & peratope mixture) | |||

|

o3o5/2o & o3o5/3o | ofx3xoo5/2ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo5/3ooo&#xt = giku | vertex figure of s3s4o3o5/2o | |

| ofx3xoo5/3xxx&#xt = qridaquit gissidu | |||

| 5D | o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo&#xt = penu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o |

| ofx3xoo3xxx3ooo&#xt = sripadecu | |||

| ofx3xoo3ooo3xxx&#xt = spidasripu | |||

| ofx3xoo3xxx3xxx&#xt = pripal gripu | |||

| xoo3ofx3xoo3ooo&#xt = rapu | |||

| xoo3ofx3xoo3xxx&#xt = sripal pripu | |||

|

o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o | ofx3xoo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo3ooo *b3ooo&#xt = hexu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o4o | |

| ofx3xoo3ooo *b3xxx&#xt = ritathexu | |||

| ofx3xoo3xxx4ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo3xxx *b3xxx&#xt = ricoatahu | |||

| ofx3xoo3ooo4xxx&#xt = sidpitha sritu | |||

| ofx3xoo3xxx4xxx&#xt = prohagritu | |||

| o3o3o5o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo5&#xt = (degenerate) exu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o5o | |

| o3o4o3o | ofx3xoo4ooo3ooo&#xt = xoo3ofx3xoo4ooo&#xt = xoo3ofx3xoo *b3xoo&#xt = icou | vertex figure of s3s4o3o4o3o | |

| xoo3ofx3xoo4xxx&#xt = sritaprohu | |||

| ofx3xoo4xxx3ooo&#xt = sricoacontu | |||

| ofx3xoo4ooo3xxx&#xt = spica sricou | |||

| ofx3xoo4xxx3xxx&#xt = pricoal gricou | |||

|

o3o3o5/2o & o3o3o5/3o | ofx3xoo3ooo5/2ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo3ooo5/3ooo&#xt = gaxu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o5/2o | |

| ofx3xoo3xxx5/2ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo3xxx5/3ooo&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo3ooo5/2xxx&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo3ooo5/3xxx&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo3xxx5/3xxx&#xt = ... | |||

| xoo3ofx3xoo5/2ooo&#xt = xoo3ofx3xoo5/3ooo&#xt = raggixu | |||

| xoo3ofx3xoo5/3xxx&#xt = ... | |||

|

o3o5/2o5o & o3o5/3o5o | ofx3xoo5/2ooo5ooo&#xt = ofx3xoo5/3ooo5ooo&#xt = gofixu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o5/2o5o | |

| ofx3xoo5/3xxx5ooo&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo5/2ooo5xxx&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo5/3ooo5xxx&#xt = ... | |||

| ofx3xoo5/3xxx5xxx&#xt = ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o5/2*b & o3o3o3/2o5/3*b | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo5/2*b&#xt = ofx3xoo3ooo3/2ooo5/3*b&#xt = sidtixhiu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o5/2*d | |

| ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o5/4*b & o3o3o3/2o5*b | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo5/4*b&#xt = ofx3xoo3ooo3/2ooo5*b&#xt = gidtixhiu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o5/4*d | |

| ... | |||

|

o3o5o3o5/3*b & o3o5o3/2o5/2*b | ofx3xoo5ooo3ooo5/3*b&#xt = ofx3xoo5ooo3/2ooo5/2*b&#xt = dittadiu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o5o3o5/3*d | |

| ... | |||

| 6D | o3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = hixu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o |

| xoo3ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo&#xt = rixu | |||

| ooo3xoo3ofx3xoo3ooo&#xt = dotu | |||

| ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3ooo3ooo *b3xoo3ofx&#xt = tacu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o4o | |

| xoo3ofx3xoo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3xoo3ooo *b3ofx3xoo&#xt = ratu | |||

| ofx3xoo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo&#xt = hinu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o *d3o3o | ||

| ... | |||

| 7D | o3o3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = hopu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o3o |

| ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3ooo3ooo *b3ooo3xoo3ofx&#xt = gu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o4o | |

| ofx3xoo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = haxu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o *d3o3o3o | ||

| ... | |||

| o3o3o3o3o *c3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo&#xt = jaku | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o *e3o | |

| xoo3ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo&#xt = rojaku | |||

| ooo3ooo3xoo3ooo3ooo *c3ofx&#xt = mou | vertex figure of o3o3o3o3o *c3o4s3s | ||

| ... | |||

| 8D | o3o3o3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = ocu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o3o3o |

| ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3ooo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo3xoo3ofx&#xt = zu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o3o4o | |

| ofx3xoo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = hesu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o *d3o3o3o3o | ||

| ... | |||

| o3o3o3o *c3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = laqu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o *e3o3o3o | |

| ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo *c3xoo3ofx3xoo&#xt = ranqu | |||

| ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo3xoo3ofx&#xt = naqu | vertex figure of o3o3o3o *c3o3o3o4s3s | ||

| ... | |||

| 9D | o3o3o3o3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = enu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o3o3o3o |

| ... | |||

|

o3o3o3o3o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo4ooo&#xt = ooo3ooo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo3ooo3xoo3ofx&#xt = eku | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o3o3o3o4o | |

| ofx3xoo3ooo *b3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = hoctu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o *d3o3o3o3o3o | ||

| ... | |||

| o3o3o3o *c3o3o3o3o | ofx3xoo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = bayu | vertex figure of s3s4o3o3o3o *e3o3o3o3o | |

| ooo3ooo3ooo3ooo *c3ooo3ooo3xoo3ofx&#xt = fyu | vertex figure of o3o3o3o *c3o3o3o3o4s3s | ||

| ... | |||

It happens that ursatopes are orbiform in general (or, if they would contain non-unit edges, at least circumscribable). E.g. for the non-expanded ursatopes one even can calculate their full-dimensional circumradius R from the subdimensional circumradius r of the quasiregular base according to: R2 = f2 (f r2 + 1/4) / (f2 - r2) , where f = (1+sqrt(5))/2 = 1.618034 is the golden ratio. That one moreover shows that those axial versions with H4 across symmetry don't exist, because those become degenerate (having zero heights) – simply because there one has r = f. This already got reflected within point 2 of the preconditions.

The tutsatopes (or tutisms) are a quite similar genuinely bistratic polytopic family as the ursatopes. They just substitute within their role the teddies by tuts. The accordingly changed necessary and sufficient conditions then reads like this:

But this class of polytopes happens to be describable in a closed form. In fact those are nothing but the P-first bistratic caps of Q, where P clearly is just that quasiregular base of the tutsatope, and Q can be obtained in Dynkin symbol description from that of P by adding to that single ringed node a further leg, marked 3, the other end of which has to be ringed as well: E.g. the dot-based tutsatope ooo3oox3xux3oox3ooo&#xt is just the dot-first bistratic cap of tim.

These base tutsatopes could be understood even better. Let P be again that quasiregular base. Then the tutsatope is defined as P || u-scaled P || truncated P. But this in turn is nothing but the truncation of point || P, i.e. of the P pyramid.

Again those base tutsatopes could be subject to Stott expansions within the across subsymmetry. Here the implied additional ringings on the Dynkin diagram of the base layer P can be correspondingly transfered onto that of Q.

Therefore both, all the base tutsatopes and all their expansions, trivially are orbiform in general.

|

across symmetry | tutsatopes | comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D | o | xux&#xt = {6} = hig | (full) x3x = {6} – vertex figure of o3o3x3*a |

| 3D | o o | xux xxx&#xt = hip | (full) x3x x = hip |

| o3o | xux3xoo&#xt = tut | (full) x3x3o = tut – vertex figure of o3o3o3x3*b | |

| 4D | o3o o | xux3xoo xxx&#xt = tuttip | (full) x3x3o x = tuttip |

| o3o3o | xux3xoo3ooo&#xt = tip | (full) x3x3o3o = tip – vertex figure of o3o3o3o3x3*c | |

| xux3xoo3xxx&#xt = coatotum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3x | ||

| o3o4o | xux3xoo4ooo&#xt = xoo3xux3xoo&#xt = octum | rotunda of x3x3o4o | |

| xux3xoo4xxx&#xt = sircoa gircotum | bistratic cap of x3x3o4x | ||

| o3o5o | xux3xoo5ooo&#xt = iktum | bistratic cap of x3x3o5o | |

| xux3xoo5xxx&#xt = srida gridtum | bistratic cap of x3x3o5x | ||

| 5D | o3o3o3o | xux3xoo3ooo3ooo&#xt = tix | (full) x3x3o3o3o = tix – vertex figure of o3o3o3o3o3x3*d |

| xux3xoo3xxx3ooo&#xt = sripa griptum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3x3o | ||

| xux3xoo3ooo3xxx&#xt = spida priptum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3o3x | ||

| xux3xoo3xxx3xxx&#xt = pripa gippidtum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3x3x | ||

| xoo3xux3xoo3ooo&#xt = raptum | bistratic cap of x3x3o *b3o3o | ||

| xoo3xux3xoo3xxx&#xt = sripa gippidtum | bistratic cap of x3x3o *b3o3x | ||

|

o3o3o4o & o3o3o *b3o | xux3xoo3ooo4ooo&#xt = xux3xoo3ooo *b3ooo&#xt = hextum | rotunda of x3x3o3o4o | |

| xux3xoo3ooo *b3xxx&#xt = ritatahtum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3o *c3x | ||

| xux3xoo3xxx4ooo&#xt = xux3xoo3xxx *b3xxx&#xt = ricoa ticotum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3x4o | ||

| xux3xoo3ooo4xxx&#xt = sidpitha prittum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3o4x | ||

| xux3xoo3xxx4xxx&#xt = proha gidpithtum | bistratic cap of x3x3o3x4x | ||

| o3o4o3o | xux3xoo4ooo3ooo&#xt = xoo3xux3xoo4ooo&#xt = (degenerate) ictum | bistratic "cap" of x3x3o4o3o | |

| 6D | o3o3o3o3o | xux3xoo3ooo3ooo3ooo&#xt = til | (full) x3x3o3o3o3o = til – vertex figure of o3o3o3o3o3o3x3*e |

| ooo3xoo3xux3xoo3ooo&#xt = dotum | bistratic cap of o3o3x3o3o *c3x | ||

| xxx3xoo3xux3xoo3ooo&#xt = sarxa gippixtum | bistratic cap of x3o3x3o3o *c3x | ||

| ... | |||

| ... | |||

It happens that those axial versions with F4 across symmetry don't exist, because those become degenerate (having zero heights). This already got reflected within point 2 of the preconditions.

Like teddi = ofx3xoo&#xt gave rise for the familly of convex bistratic orbiform ursatopes and tut = xux3xoo&#xt gave rise for the familly of convex bistratic orbiform tutsatopes, trippescu = reduced( ofx3/2oxx&#xt by {6/2} ) too provides an according familly of non-convex bistratic orbiform polytopes. This series was initiated by "puffer fish" in late 2021.

|

across symmetry | familly member | |

|---|---|---|

| 2D | o | ofx&#xt = {5} = peg |

| 3D | o o | ofx xxx&#xt = pip |

| o3/2o | reduced( ofx3/2oxx&#xt by {6/2} ) = trippescu | |

| 4D | o3/2o3o | reduced( ofx3/2oxx3ooo&#xt by {6/2} ) |

| reduced( ofx3/2oxx3xxx&#xt by {6/2} ) | ||

| o3/2o4o | reduced( ofx3/2oxx4ooo&#xt by oct+6{4} ) | |

| ... | ||

| ... | ||

Like teddi = ofx3xoo&#xt gave rise for the familly of convex bistratic orbiform ursatopes and tut = xux3xoo&#xt gave rise for the familly of convex bistratic orbiform tutsatopes, and just above trippescu = reduced( ofx3/2oxx&#xt by {6/2} ) gave rise for the familly of generally non-convex bistratic orbiforms of the trippescu series, so too pero = ofx5xox&#xt provides an according familly of bistratic orbiform polytopes. Although this series well has convex members too, because of the large circumradius of pero itself, it naturally also gives rise to re-entrant members as well.

|

across symmetry | familly member | |

|---|---|---|

| 2D | o | ofx&#xt = {5} = peg |

| 3D | o o | ofx xxx&#xt = pip |

| o5o | ofx5xox&#xt = pero | |

| 4D | o5o3o | ofx5xox3ooo&#xt = biscrahi |

| ofx5xox3xxx&#xt = arse biscrahi | ||

| xox5ofx3xoo&#xt = tiduro (ursatope & peratope mixture) | ||

|

o5o5/2o & o5o5/3o | ofx5xox5/2ooo&#xt = ofx5xox5/3ooo&#xt = biscrighi | |

| ofx5xox5/3xxx&#xt = arsque biscrighi | ||

| reduced( ofx5xox5/2xxx&#xt, by x5/2x ) = bisc sridtathi | ||

| ... | ||

In late 2025 B. Klein came up with the idea for a series around a further small bistratic polyhedron, ebot = xux xo(-x)&#xt. He already considered most of the following:

|

across symmetry | familly member | |

|---|---|---|

| 3D | o o | xux xo(-x)&#xt = ebot |

| 4D | o o5o | xux ooo5xo(-x)&#xt |

| reduced( xux xxx5xo(-x)&#xt by 2stip ) | ||

| o3o o | xux3xoo xo(-x)&#xt = sripper | |

| o3o5/2o | reduced( xux3xoo5/2xo(-x)&#xt by 2peppy ) | |

| o3o3o | reduced( xux3xoo3xo(-x)&#xt by 2thah ) (degenerate) | |

| ... | ||

These can be considered as dissected bipyramids with a squeezed in equatorial prism. Therefore, whenever the bipyramid was Dynkin describable, the elongated one will be too, just double up the medial vertex layer symbol at each node position. I.e. whenever the (sectional) base had an x, then the pyramid would have an ox, the bipyramid an oxo, and the elongated bipyramid would require an oxxo node. (Similar for o nodes.)

For convex elongated bipyramids, which generally are external blends of segmentotopes, we have:

| 2D | ohho&#xt | pt || h-line || h-line || pt | 6g |

| 3D | oxxo3oooo&#xt | pt || 3g || 3g || pt | etidpy (J14) |

| oxxo4oooo&#xt | pt || 4g || 4g || pt | esquidpy (J15) | |

| oxxo5oooo&#xt | pt || 5g || 5g || pt | epedpy (J16) | |

| 4D | oxxo3oooo3oooo&#xt | pt || tet || tet || pt | etedpy |

| oxxo3oooo4oooo&#xt | pt || oct || oct || pt | pex hex | |

| oxxo4oooo3oooo&#xt | pt || cube || cube || pt | ecubedpy | |

| oxxo3oooo5oooo&#xt | pt || ike || ike || pt | eikedpy | |

| - | pt || squippy || squippy || pt | esquippidpy | |

| - | pt || pap || pap || pt | epapdapy (?) | |

| - | pt || gyepip (J11) || gyepip (J11) || pt | egyepipdapy (?) | |

| - | pt || mibdi (J62) || mibdi (J62) || pt | emibdidpy (?) | |

| - | pt || teddi (J63) || teddi (J63) || pt | eteddidpy (?) | |

| oxxo oxxo3oooo&#xt | pt || trip || trip || pt | etripdapy | |

| oxxo oxxo5oooo&#xt | pt || pip || pip || pt | epipdapy |

In the research for n/d,n/d,3-acrohedra – an acrohedron is a polyhedron containing acrons (or vertices), where acron stems from Greek ακροσ (acros, i.e. summit), as in Acropolis – M. Green found in October 2005 an 7,7,3-acrohedron, which he called a supersemicupola. Based on that finding a small family of n/d,n/d,3-acrohedra was set up according the generalized building rules thereof:

Clearly n/d only ranges according to 12/5 < n/d < 12, as in those extremal values the acrons would become flat.

For cases with n being even there generaly would be an easier acrohedron too. In fact, those according to Green's rule then just describes a gyrated blend of 2 such easier ones. (This is quite similar as for the cupolaic blends.)

The following list provides the known n/d,n/d,3-acrohedra which follow that Green's rule.

| {n/d} | Name | (related acrohedron) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3/1 | (degenerate): just the Grünbaumian double-covered skin-surface of the 3-fold pyramid |  | tetrahedron |

| 4/1 | tutrip, "Phillips head" |  | trigonal prism (as digonal cupola) |

| 5/1 | ike-faceting ike-5-5 |  | (none) |

| 5/2 | sissid-faceting sissid-5-5 |  | (none) |

| 6/1 | tutut (has a membrane) |  | truncated tetrahedron |

| 7/1 | sissicu (has a membrane) |  | 28T-15H-7sH |

| 7/2 | gissicu |  | 28T-15sH-7gH |

| 8/1 | tutic (is a tube) |  | truncated cube |

| 8/3 | tuquith |  | quasitruncated cube |

| 10/1 | tutid (is a tube) |  | truncated dodecahedron |

| 10/3 | tuquit gissid |  | quasitruncated great stellated dodecahedron |

Already in 2005 Mason Green discovered this series of chiral, regular faced polyhedra (cf. here), then calling them "cingulated antiprisms". His naming derived from cutting open the lacing zig-zag, re-connecting these parts by a strip (cingulum) of 4n triangles.

In 2025 a discord member calling himself "Harsin sinquin" came up with those polyhedra again. But now their construction was derived a bit different. In fact those now are based by concept on a central (chiral isogonal variant of an) antiprism plus lateral, chirally attached wedges from 6 triangles. Here the lacing zig-zag of the antiprism variant alternates with x-sized (for up) and y-sized (for down) edges, where the x-edges have the same size as the base edges, while the length of the y-edges is free to be adjusted secondarily. The wedges now burry those y-edges underneath, so that the result becomes all unit-edged again. In fact, the requirement that those wedge-triangles all are regular ones as well, thereby settles the size of those (internal) y-edges after all.

The Greek root for wedge, being "spheno" is already getting used, esp. within Johnson solids, in fact then refering to lune-based ones. Moreover, in the context of polychora that Greek term has already been used in a different wedge-sense meaning as well. Thence, in order not to further mix up that reading, the Latin root for wedge, being "cune" had now been taken over.

These cuneprisms generally have a single concave edge type and always are biform (i.e. same as uniform, except that there are 2 different vertex types).

n/d-cuneprism 2n * | 2 1 1 1 1 0 | 1 2 2 1 [n,35] * 2n | 0 0 1 1 1 1 | 0 1 1 2 [34] ------+-----------------+----------- 2 0 | 2n * * * * * | 1 1 0 0 ry 2 0 | * n * * * * | 0 0 2 0 gg (concave) 1 1 | * * 2n * * * | 0 1 1 0 yg 1 1 | * * * 2n * * | 0 1 0 1 yb 1 1 | * * * * 2n * | 0 0 1 1 gb 0 2 | * * * * * n | 0 0 0 2 bb ------+-----------------+----------- n 0 | n 0 0 0 0 0 | 2 * * * (red ) 2 1 | 1 0 1 1 0 0 | * 2n * * (yellow ) 2 1 | 0 1 1 0 1 0 | * * 2n * (green ) 1 2 | 0 0 0 1 1 1 | * * * 2n (blue )

or (as tower): n * * * | 2 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 | 1 2 1 1 1 0 0 0 [n,35] * n * * | 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 | 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 [34] * * n * | 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 | 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 [34] * * * n | 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 2 | 0 0 0 1 1 1 2 1 [n,35] --------+---------------------+---------------- 2 0 0 0 | n * * * * * * * * * | 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 ry 1 1 0 0 | * n * * * * * * * * | 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 yg 1 1 0 0 | * * n * * * * * * * | 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 yb 1 0 1 0 | * * * n * * * * * * | 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 gb 1 0 0 1 | * * * * n * * * * * | 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 gg (concave) 0 1 1 0 | * * * * * n * * * * | 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 bb 0 1 0 1 | * * * * * * n * * * | 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 gb 0 0 1 1 | * * * * * * * n * * | 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 yg 0 0 1 1 | * * * * * * * * n * | 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 yb 0 0 0 2 | * * * * * * * * * n | 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 ry --------+---------------------+---------------- n 0 0 0 | n 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 | 1 * * * * * * * (red ) 2 1 0 0 | 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 | * n * * * * * * (yellow ) 1 1 1 0 | 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 | * * n * * * * * (blue ) 1 1 0 1 | 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 | * * * n * * * * (green ) 1 0 1 1 | 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 | * * * * n * * * (green ) 0 1 1 1 | 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 | * * * * * n * * (blue ) 0 0 1 2 | 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 | * * * * * * n * (yellow ) 0 0 0 n | 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 n | * * * * * * * 1 (red )

When re-considering this latter construction-wise re-adjustment of these burried pseudo y-edges, it becomes apparent, that this series of cuneprisms after all even can be generalised towards cune twisters as well. (At least those then seem to be new indeed.)

© 2004-2026 | top of page |